Roger Eduardo Molina**-**Acevedo and his girlfriend, Daniela Núñez, arrived at a Houston airport less than two weeks before Trump was inaugurated.

The couple had wanted to start a new life in the U.S., but only if they could do so legally.

They had applied to resettle through a State Department-run program called the Safe Mobility Initiative that spent several months vetting them through security checks and face-to-face interviews while they were living in Colombia.

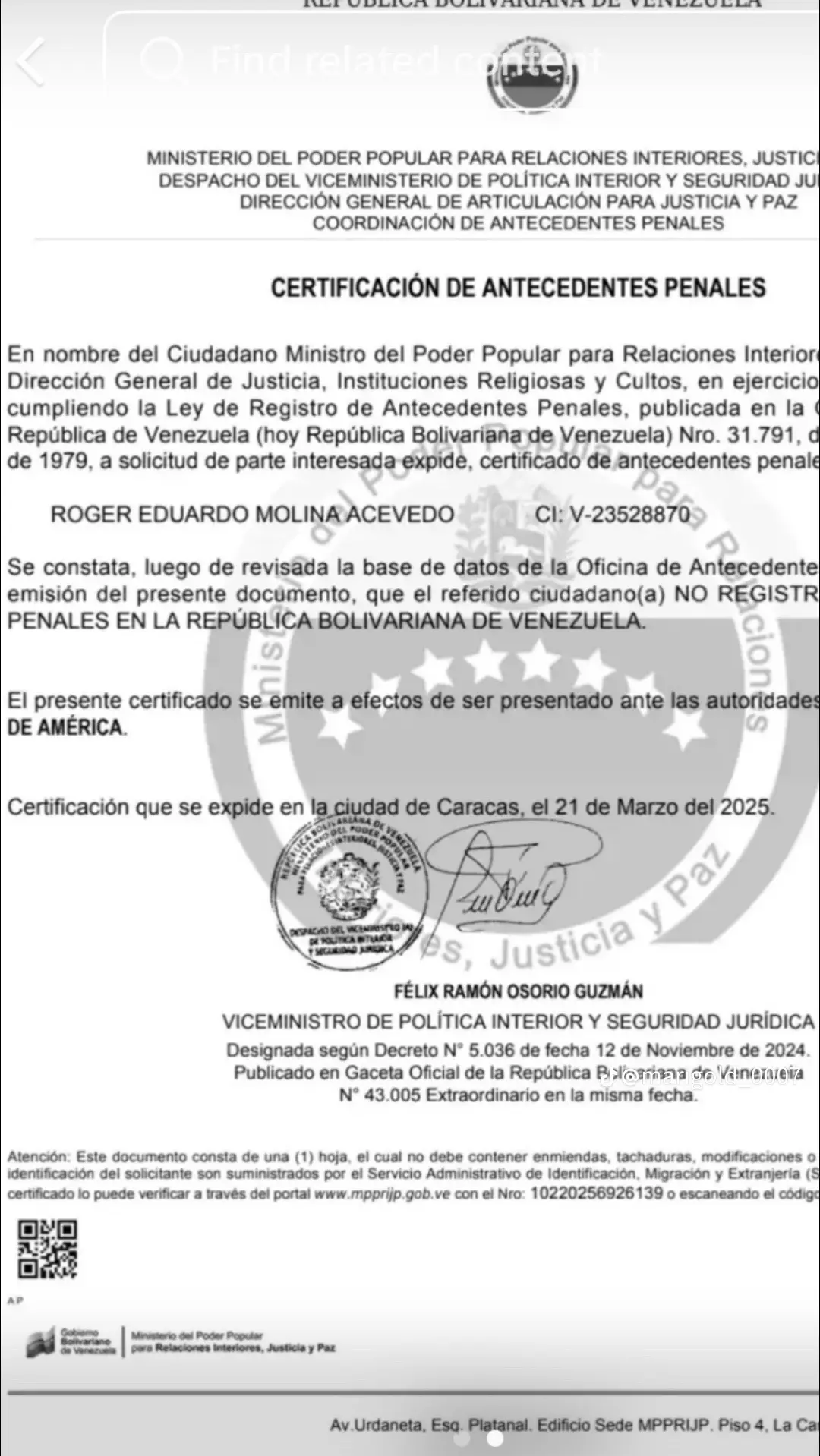

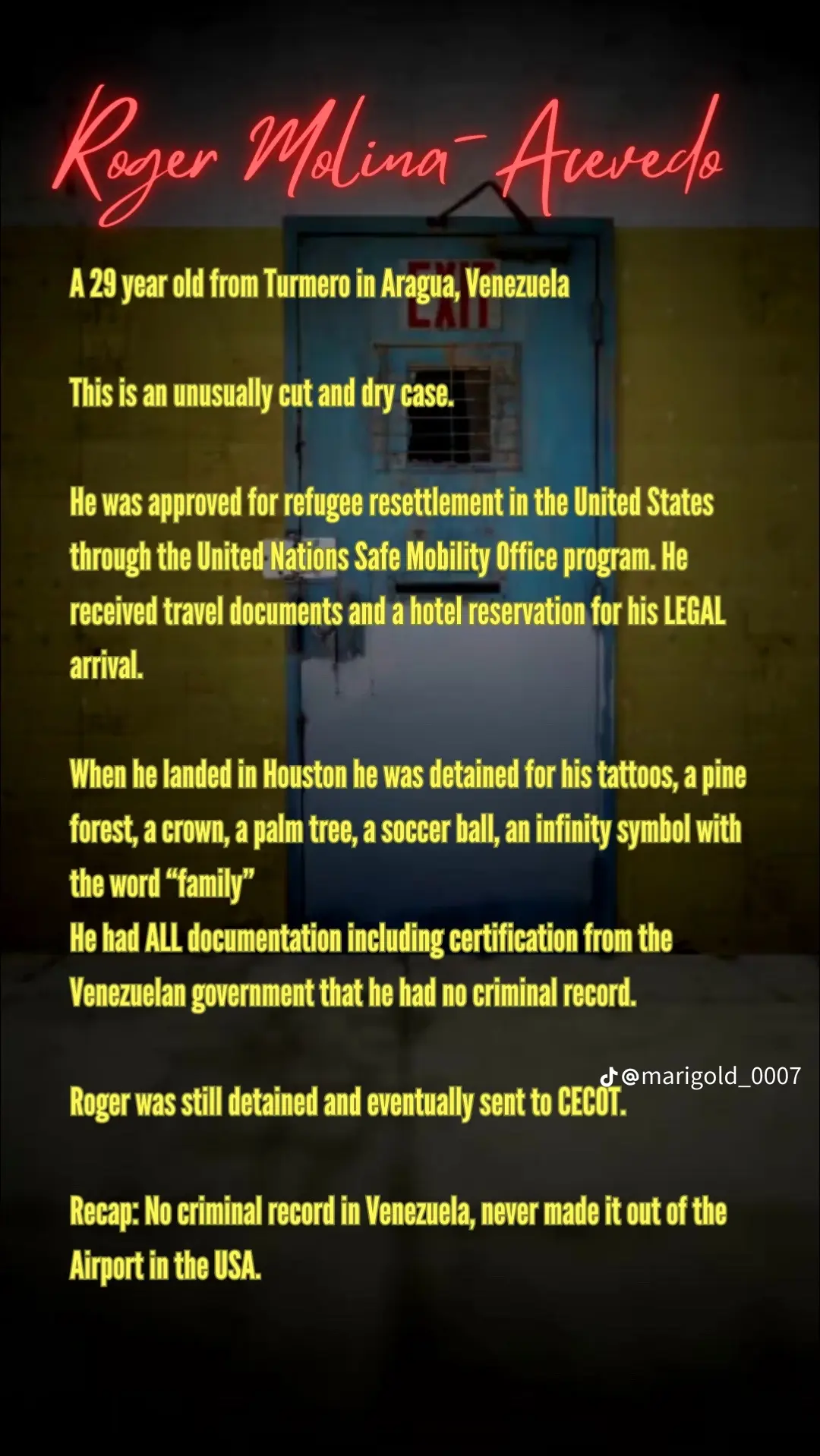

Under Safe Mobility, a program that Trump recently discontinued, migrants were interviewed, and had to show overwhelming evidence of persecution in their home country as well as documentation of work history and a clean criminal record. The criteria were very strict, the process was long, thorough and cumbersome, and only a small percentage of applicants were accepted.

In September, Roger and Daniella were approved for refugee status and, after completing the final clearances, given plane tickets to Texas.

“It was a huge blessing,” said Daniela, 30.

Molina, 29, was not politically outspoken, but his family said he caught the ire of a local official aligned with Maduro after he organized a fundraiser on Facebook to improve the soccer field where he played. The official saw Molina’s fundraiser as a jab at the government and its poor maintenance of public spaces. Molina began receiving threats on WhatsApp, Daniela said. The couple fled to Colombia in 2021.

They were prepared to start over again when they arrived in Texas on Jan. 8, in the last days of the Biden administration. Then they were stopped by a CBP officer at the Houston airport.

The officer asked Roger whether he had any tattoos. He showed him the crown on his chest, the soccer ball and forest on his wrists, the palm tree on one ankle and the infinity sign inscribed with the word “family” on the other.

The officer told them the tattoos were associated with Tren de Aragua, recalled Núñez, who witnessed one of Molina’s conversations with a CBP officer.

Next the agent looked through his phone. In a WhatsApp group chat that included several friends, Molina had once made a joke about the hamburgers he sold to help support his family. He told his friends that if they didn’t buy his burgers, Tren de Aragua would come after them.

It was the kind of joke heard often among Venezuelans living in Latin America, the couple told the agent.

“These aren’t the kinds of jokes we make in my family,” the officer said.

The officer detained Roger for further questioning. Núñez was told she could either wait in U.S. detention for her case to be sorted out or could return to Colombia that day. She chose the latter. Roger wasn’t given the option.

Another official asked him whether he was afraid of returning to Venezuela, he later told Núñez. When he responded yes, he was informed he would be taken into custody while his case was adjudicated. Three lawyers with extensive experience in refugee law told the Washington Post they had never heard of a vetted refugee being arrested on arrival.

Jenny Coromoto Acevedo, Roger’s mother said on TikToc:

Roger “was detained in the United States, in the state of Texas. There, on Thursday, March 13, my son called me and told me that he had received a notice that he was going to be deported to his home country because flights were already scheduled for Venezuela. When I hadn’t heard from my son all day, which seemed strange to me because he communicated with me every day, around 6:30 p.m., I searched the app, I searched the system, and it said my son had been transferred to another detention center.”

“He was transferred to the East Hidalgo detention center in Texas. I called immediately and they confirmed that yes, my son had been sent there, but that I couldn’t contact him until Monday because he had been there so recently and couldn’t reach me.”

“That seemed odd to me because on other occasions when they transferred him to another center, he would call immediately. They would allow them a call to a relative. We made sure he could contact us.”

“So, I was walking around on Saturday, Sunday, without knowing anything about him. Yesterday, Monday [March 17], first thing in the morning, I called and they told me my son isn’t at that center. I searched the [online detention locator] system and his name still showed up. I looked for other ways to see if he really isn’t there. Calling here and there, they told me that my son, that he’s no longer in the United States.”

A few days later, the family learned that Roger had been sent to the CECOT in El Salvador when they saw his name on the leaked list of deportees. Roger’s mother insists that he is innocent, and he is being unjustly accused of gang membership simply for having tattoos.

Roger’s uncle said in an Instagram video about Roger:

“His father, his mother, are desperate for that boy. Something must be done because, in the same situation, my nephew and many other innocent young people who were only looking for a better future are now in El Salvador without knowing what will happen to them.

And well, we demand justice, that the voices of all Venezuelans be heard, because now, just because we are Venezuelans, we are criminals; it’s not fair.”

Roger Eduardo Molina-Acevedo y su novia, Daniela Núñez, llegaron a un aeropuerto de Houston menos de dos semanas antes de que Trump fuera investido.

La pareja quería comenzar una nueva vida en los EE. UU., pero solo si podían hacerlo legalmente.

Habían solicitado reasentarse a través de un programa dirigido por el Departamento de Estado llamado Iniciativa de Movilidad Segura que pasó varios meses evaluándolos a través de controles de seguridad y entrevistas en persona mientras vivían en Colombia.

Bajo Safe Mobility, un programa que Trump recientemente descontinuó, los migrantes eran entrevistados y tenían que mostrar evidencia abrumadora de persecución en su país de origen, así como documentación de historial laboral y un récord criminal limpio. Los criterios eran muy estrictos, el proceso era largo, exhaustivo y engorroso, y solo un pequeño porcentaje de solicitantes eran aceptados.

En septiembre, Roger y Daniella fueron aprobados para el estatus de refugiado y, después de completar los permisos finales, les dieron boletos de avión a Texas.

“Fue una gran bendición”, dijo Daniela, de 30 años.

Molina, de 29 años, no era políticamente hablador, pero su familia dijo que atrajo la ira de un funcionario local alineado con Maduro después de organizar una recaudación de fondos en Facebook para mejorar el campo de fútbol donde jugaba. El funcionario vio la recaudación de fondos de Molina como un golpe al gobierno y su pobre mantenimiento de los espacios públicos. Molina comenzó a recibir amenazas en WhatsApp, dijo Daniela. La pareja huyó a Colombia en 2021.

Estaban preparados para comenzar de nuevo cuando llegaron a Texas el 8 de enero, en los últimos días de la administración de Biden. Luego fueron detenidos por un oficial de la CBP en el aeropuerto de Houston.

El oficial le preguntó a Roger si tenía tatuajes. Le mostró la corona en su pecho, el balón de fútbol y el bosque en sus muñecas, la palmera en un tobillo y el signo de infinito inscrito con la palabra “familia” en el otro.

El oficial les dijo que los tatuajes estaban asociados con Tren de Aragua, recordó Núñez, quien presenció una de las conversaciones de Molina con un oficial de la CBP.

Luego, el agente revisó su teléfono. En un chat de grupo de WhatsApp que incluía a varios amigos, Molina una vez hizo una broma sobre las hamburguesas que vendía para ayudar a mantener a su familia. Les dijo a sus amigos que si no compraban sus hamburguesas, Tren de Aragua iría tras ellos.

Era el tipo de broma que se escuchaba a menudo entre los venezolanos que vivían en América Latina, dijo la pareja al agente.

“Estos no son los tipos de bromas que hacemos en mi familia”, dijo el oficial.

El oficial detuvo a Roger para un interrogatorio adicional. A Núñez se le dijo que podía esperar en detención en EE. UU. para que se resolviera su caso o podía regresar a Colombia ese día. Ella eligió lo último. A Roger no se le dio la opción.

Otro funcionario le preguntó si tenía miedo de regresar a Venezuela, le dijo más tarde a Núñez. Cuando respondió que sí, se le informó que sería detenido mientras se resolvía su caso. Tres abogados con amplia experiencia en leyes de refugiados le dijeron al Washington Post que nunca habían oído hablar de un refugiado verificado siendo arrestado a su llegada.

Jenny Coromoto Acevedo, la madre de Roger, dijo en TikToc:

Roger “fue detenido en los Estados Unidos, en el estado de Texas. Allí, el jueves 13 de marzo, mi hijo me llamó y me dijo que había recibido un aviso de que iba a ser deportado a su país de origen porque ya se habían programado vuelos para Venezuela. Cuando no había tenido noticias de mi hijo durante todo el día, lo cual me pareció extraño porque se comunicaba conmigo todos los días, alrededor de las 6:30 p.m., busqué en la aplicación, busqué en el sistema, y decía que mi hijo había sido trasladado a otro centro de detención”.

“Fue trasladado al centro de detención de East Hidalgo en Texas. Llamé de inmediato y confirmaron que sí, mi hijo había sido enviado allí, pero que no podía contactarlo hasta el lunes porque había estado allí recientemente y no podía comunicarse conmigo”.

“Eso me pareció extraño porque en otras ocasiones cuando lo trasladaban a otro centro, llamaba de inmediato. Les permitían una llamada a un familiar. Nos asegurábamos de que pudiera contactarnos”.

“Así que estuve dando vueltas el sábado, domingo, sin saber nada de él. Ayer, lunes [17 de marzo], lo primero en la mañana, llamé y me dijeron que mi hijo no está en ese centro. Busqué en el sistema [localizador de detención en línea] y su nombre seguía apareciendo. Busqué otras formas de ver si realmente no estaba allí. Llamando aquí y allá, me dijeron que mi hijo, que ya no está en los Estados Unidos”.

Unos días después, la familia se enteró de que Roger había sido enviado al CECOT en El Salvador cuando vieron su nombre en la lista filtrada de deportados. La madre de Roger insiste en que es inocente y que se le acusa injustamente de pertenecer a una pandilla simplemente por tener tatuajes.

El tío de Roger dijo en un video de Instagram sobre Roger:

“Su padre, su madre, están desesperados por ese chico. Algo debe hacerse porque, en la misma situación, mi sobrino y muchos otros jóvenes inocentes que solo buscaban un futuro mejor ahora están en El Salvador sin saber qué les sucederá.

Y bueno, exigimos justicia, que se escuchen las voces de todos los venezolanos, porque ahora, solo porque somos venezolanos, somos criminales; no es justo”.