His family believes the detention was linked to Luis’s tattoos, particularly a crown on his chest—inked years ago with an ex-partner—which authorities wrongly associated with gangs. Experts say Venezuelan gangs are not identified by tattoos, yet the crown symbol has been targeted by law enforcement.

Luis had no criminal record and was actively pursuing asylum. On March 15, he told Ángela he might be deported to Venezuela. Days later, his name appeared in an Instagram livestream listing Venezuelans sent to El Salvador’s CECOT prison—a maximum-security facility infamous for brutal treatment.

According to reports, detainees at CECOT are abused, silenced, and denied basic necessities. Luis’s mother and partner now fear for his safety and well-being, describing their lives as shattered by his disappearance and unjust deportation.

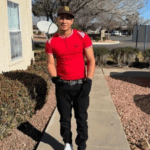

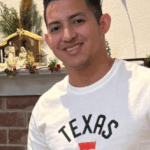

Luis Carlos José Marcano Silva (26) was born and raised on the beach-lined island of Margarita in Venezuela, situated off the coast of the South American nation, 200 miles northeast of Caracas. Like many Venezuelans, the 26-year-old was forced to leave home when Venezuela descended into a political, economic, and humanitarian crisis. In November 2023, Marcano and his girlfriend, Angela, along with their two young children, journeyed to Mexico and crossed the Rio Grande River on foot in search of a better life in the United States.

The family traveled by bus to Bradenton, Florida, where they settled down and applied for asylum. But after living and working in the coastal city for almost two years — and experiencing no issues with the immigration system. Angela explains that she, Luis, and their children attended an immigration appointment in January 2024, at which time the court scheduled another hearing for February 27 of this year.

Then, Luis received a letter from ICE’s Tampa office asking that he show up to court on February 5, 2025. When he showed up for the appointment, Angela says, he was detained and taken to a federal prison in Miami and then transported to Texas.

Angela says the family’s former attorney said Luis’ tattoos, particularly a crown inked on his chest, likely contributed to his arrest. (Angela says they stopped consulting with the lawyer because they felt they were being financially exploited.)

Luis has several tattoos: one, on his belly, depicts the face of Jesus of Nazareth; another, on his arm, displays an infinity symbol; a third bears the name of his daughter, Adelys. Angela says Luis got the crown tattoo with an ex-girlfriend in Venezuela when he was 19; his bears the phrase “Una Vida” (“One Life”), while hers says “Un Amor” (“One Love”).

Experts have said Venezuelan gangs aren’t identified by tattoos and that tattoos aren’t closely connected with affiliation to Tren de Aragua. But law enforcement officials have nonetheless included the five-point crown on a list of tattoos to help identify members of the violent gang.

Luis’ family insists that he has no affiliation whatsoever with the violent gang, which the U.S. recently classified as a foreign terrorist group. They argue the only thing Marcano ever did wrong was to enter the U.S. illegally, and that he was in the process of seeking asylum through this country’s notoriously backlogged system when he was detained.

The last time Angela spoke with him, on March 15, he was on U.S. soil and told her officials were planning to deport him back to Venezuela.

“I didn’t hear from him again,” Angela tells New Times.

Instead, days later, she spotted her his name on an Instagram livestream that listed 238 Venezuelan men who had been taken to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador — a country where Marcano had never set foot in his life.

According to photojournalist Philip Holsinger, who witnessed the men’s arrival at the El Salvador prison, guards kicked, slapped, and shoved them, then shaved their heads. Packed 80 to a cell with bare steel planks for beds and no mats or pillows, they were forbidden to speak, read, or make phone calls.

“For these Venezuelans, it was not just a prison they had arrived at. It was exile to another world, a place so cold and far from home they may as well have been sent into space, nameless and forgotten,” Holsinger wrote in a March 21 dispatch published in Time magazine. “Holding my camera, it was as if I watched them become ghosts.”

“My life was completely destroyed, and nothing will ever fix it,” Ángela said in an interview.

“I feel frustrated, desperate. I imagine they are not treating him well. I’ve already seen videos of that prison,” Adelys del Valle Silva Ortega, Luis’ mother said of the notorious Salvadoran “anti-terrorism” jail where her son is now thought to be incarcerated. “I think of him every moment, praying to the Virgin of the Valley [a Venezuelan patron saint] to protect him.”

Luis Carlos José Marcano Silva (26) nació y creció en la isla costera de Margarita, en Venezuela, ubicada a 200 millas al noreste de Caracas. Como muchos venezolanos, se vio obligado a dejar su hogar cuando Venezuela cayó en una crisis política, económica y humanitaria. En noviembre de 2023, Marcano, su novia Ángela y sus dos hijos pequeños emprendieron un viaje hacia México y cruzaron a pie el río Bravo (Río Grande) en busca de una vida mejor en Estados Unidos.

La familia viajó en autobús hasta Bradenton, Florida, donde se establecieron y solicitaron asilo. Después de vivir y trabajar allí por casi dos años sin ningún problema con el sistema migratorio, Ángela cuenta que ella, Luis y sus hijos asistieron a una cita de inmigración en enero de 2024, en la cual se programó otra audiencia para el 27 de febrero de este año.

Sin embargo, Luis recibió una carta de la oficina de ICE en Tampa, solicitándole que se presentara a una audiencia el 5 de febrero de 2025. Cuando asistió a la cita, Ángela relata que fue detenido y llevado a una prisión federal en Miami, y luego trasladado a Texas.

Ángela afirma que el abogado anterior de la familia les dijo que los tatuajes de Luis —en particular una corona tatuada en su pecho— probablemente contribuyeron a su arresto. (Ella también explicó que dejaron de consultar a ese abogado porque sentían que estaban siendo explotados económicamente).

Luis tiene varios tatuajes: uno en el abdomen con el rostro de Jesús de Nazaret; otro en el brazo con un símbolo de infinito; y otro con el nombre de su hija, Adelys. Ángela dice que Luis se hizo el tatuaje de la corona con una exnovia cuando tenía 19 años; el de él lleva la frase “Una Vida”, mientras que el de ella decía “Un Amor”.

Expertos han señalado que las pandillas venezolanas no se identifican por tatuajes y que los tatuajes no están necesariamente vinculados al Tren de Aragua. Sin embargo, las autoridades han incluido la corona de cinco puntas en una lista de tatuajes para identificar supuestos miembros de dicha pandilla violenta.

La familia de Luis insiste en que no tiene ninguna afiliación con ese grupo, el cual recientemente fue clasificado por Estados Unidos como una organización terrorista extranjera. Argumentan que lo único que hizo mal fue entrar al país de manera irregular, y que estaba en proceso de solicitar asilo dentro de un sistema migratorio notoriamente colapsado cuando fue detenido.

La última vez que Ángela habló con él fue el 15 de marzo. Luis todavía se encontraba en territorio estadounidense y le dijo que planeaban deportarlo a Venezuela.

“No volví a saber nada de él,” dijo Ángela al New Times.

Días después, vio su nombre en una transmisión en vivo por Instagram que enumeraba a 238 hombres venezolanos trasladados a una prisión de máxima seguridad en El Salvador, un país en el que Marcano nunca había estado en su vida.

Según el fotoperiodista Philip Holsinger, quien presenció la llegada de los hombres a la prisión salvadoreña, los guardias los patearon, abofetearon y empujaron, luego les raparon la cabeza. Aglomerados 80 por celda, con planchas de acero desnudas como camas y sin colchones ni almohadas, se les prohibía hablar, leer o hacer llamadas telefónicas.

“Para estos venezolanos, no era solo una prisión a la que habían llegado. Era un exilio a otro mundo, un lugar tan frío y lejano que bien podrían haber sido enviados al espacio, sin nombre ni identidad”, escribió Holsinger en un reportaje publicado el 21 de marzo en la revista Time. “Sosteniendo mi cámara, era como si los viera convertirse en fantasmas”.

“Mi vida fue completamente destruida, y nada podrá arreglarla,” dijo Ángela en una entrevista.

“Me siento frustrada, desesperada. Me imagino que no lo están tratando bien. Ya he visto videos de esa prisión,” comentó Adelys del Valle Silva Ortega, madre de Luis, sobre la notoria cárcel salvadoreña “antiterrorista” donde ahora se cree que está encarcelado su hijo. “Pienso en él a cada momento, rezándole a la Virgen del Valle para que lo proteja.”

Leave a Reply