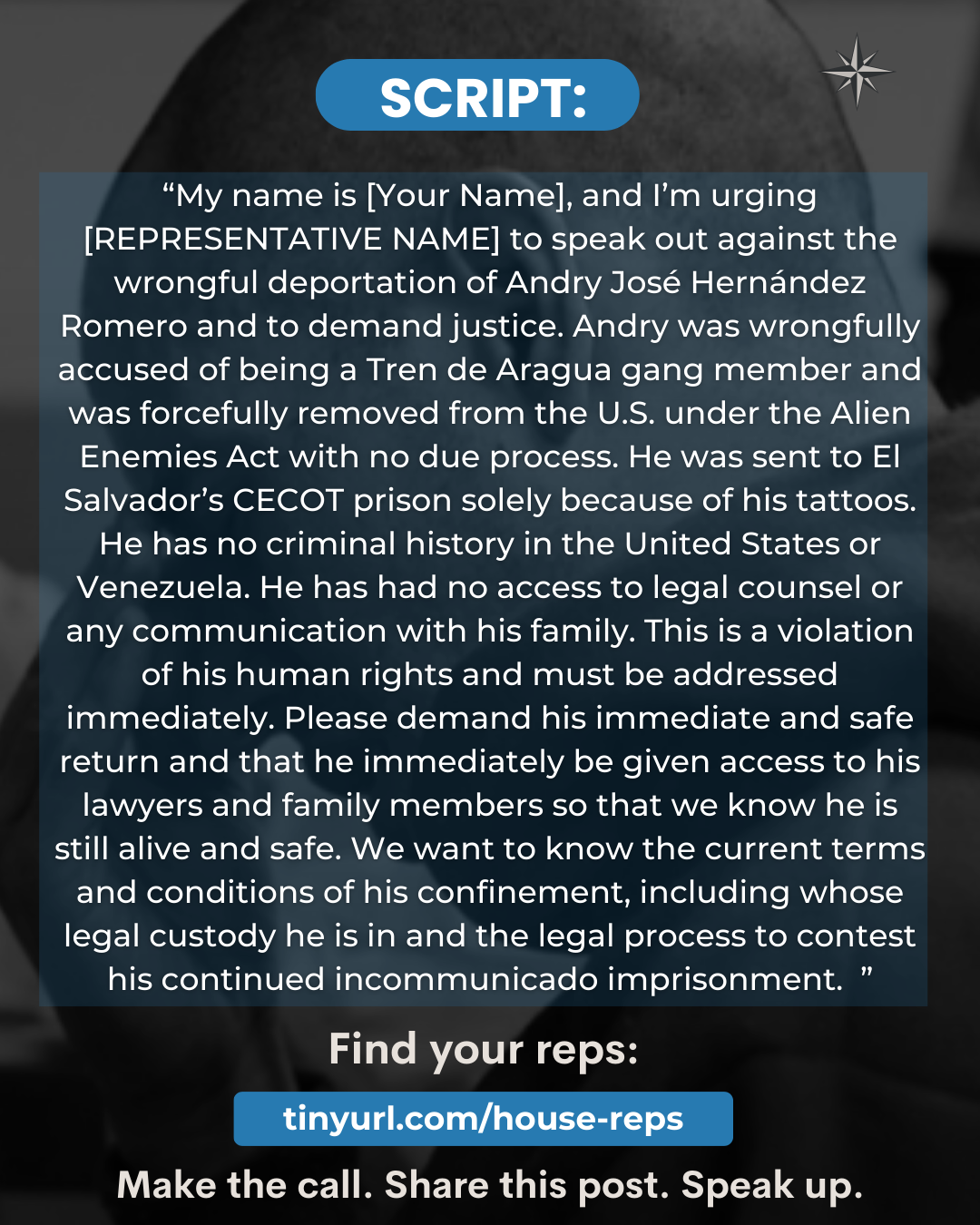

Andry was never given a chance to contest the gang allegations. In March 2025, while his asylum case was still pending, he was abruptly deported—along with 260 others—to El Salvador’s CECOT mega-prison. There, he was photographed in chains, sobbing and praying, by a U.S. journalist. Since then, no one has confirmed his whereabouts or condition.

His deportation has drawn national and international attention. California Governor Gavin Newsom has requested his return. U.S. lawmakers have sought proof of life but have been denied by Homeland Security Secretary Kristy Noem, who deflected responsibility. Andry is now a named plaintiff in a major ACLU lawsuit, J.G.G. v Trump, seeking the release of detained Venezuelan men from CECOT. Advocacy efforts include protests and fundraisers, such as events at the Stonewall Inn and an upcoming show at WorldPride in Washington, D.C.

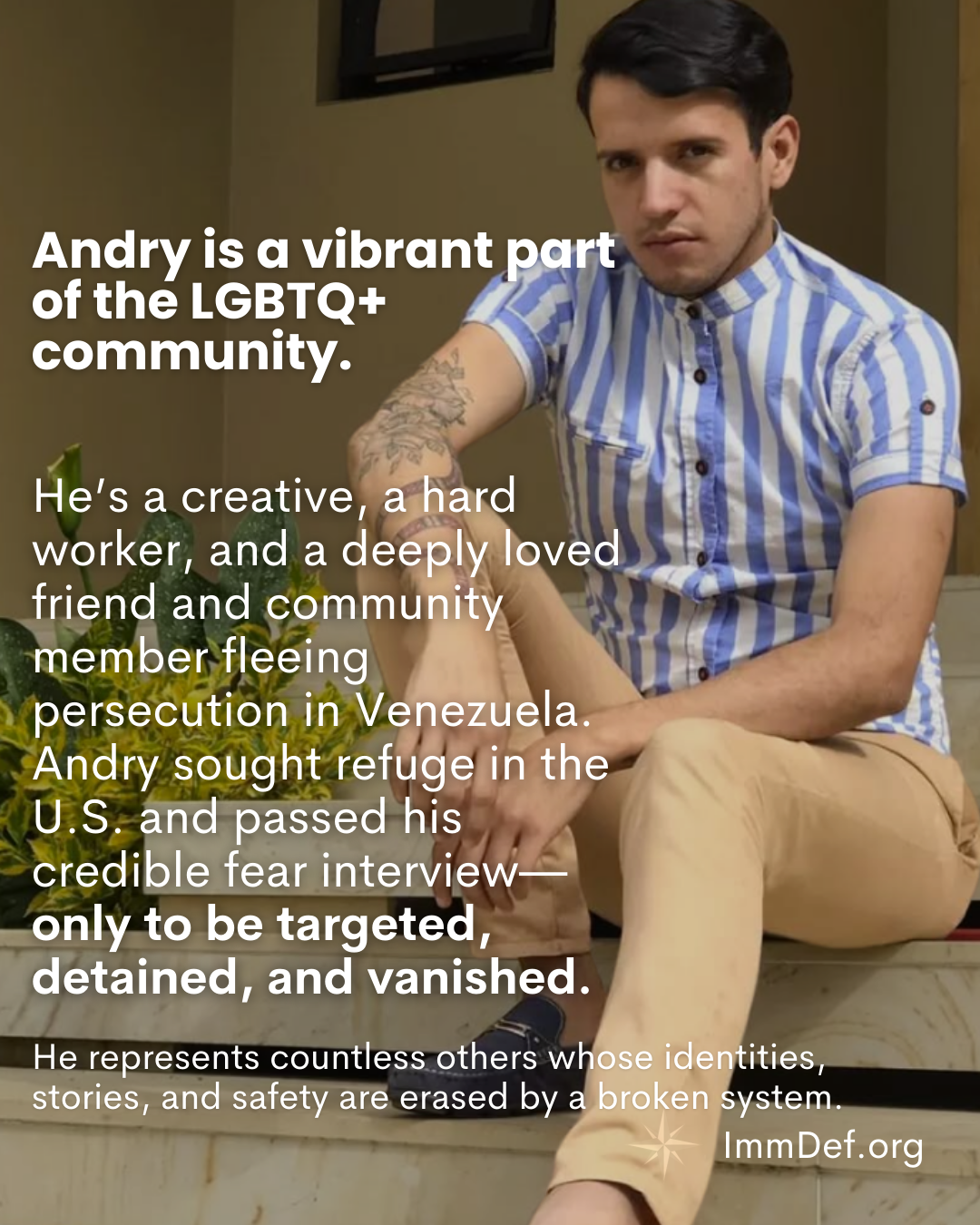

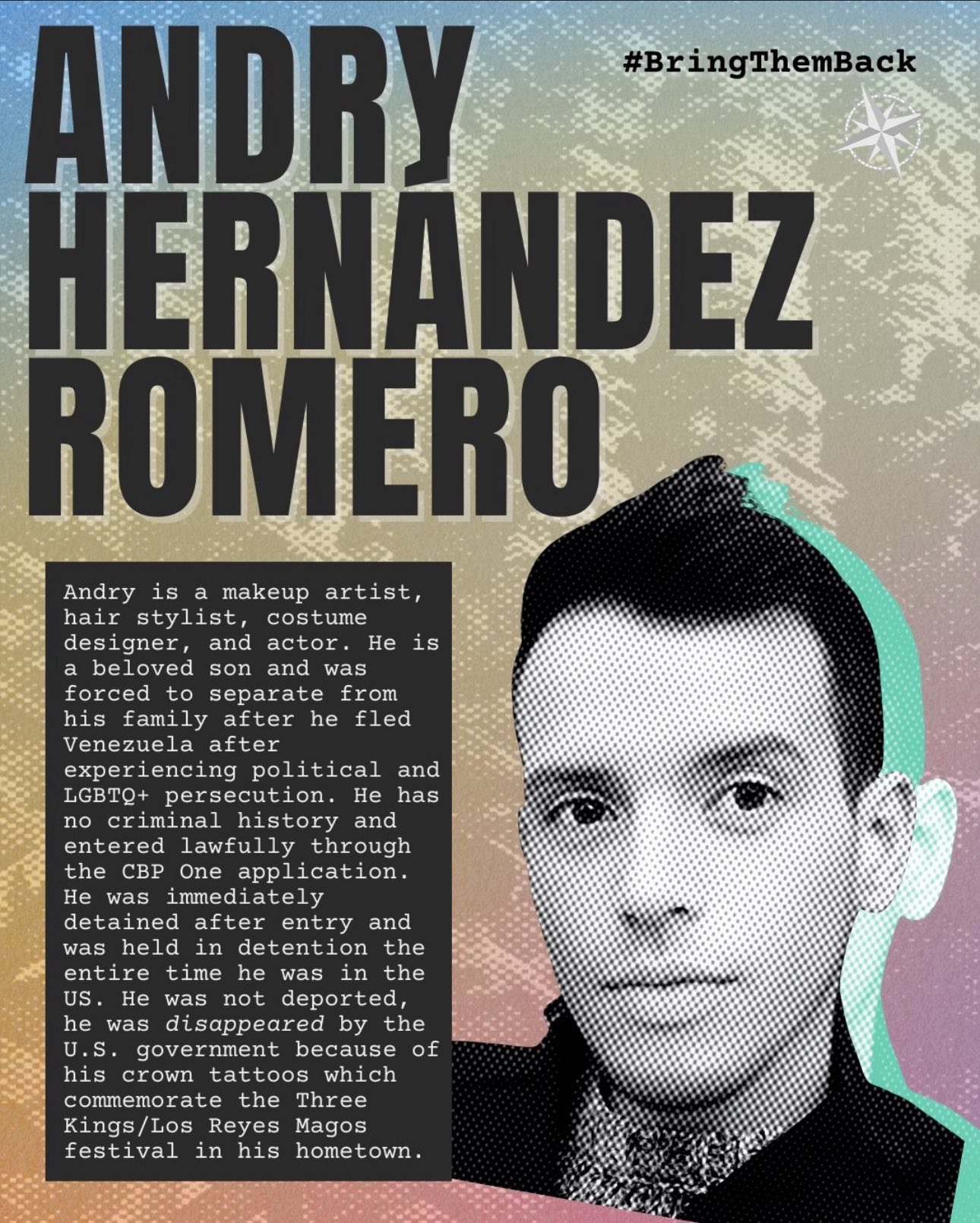

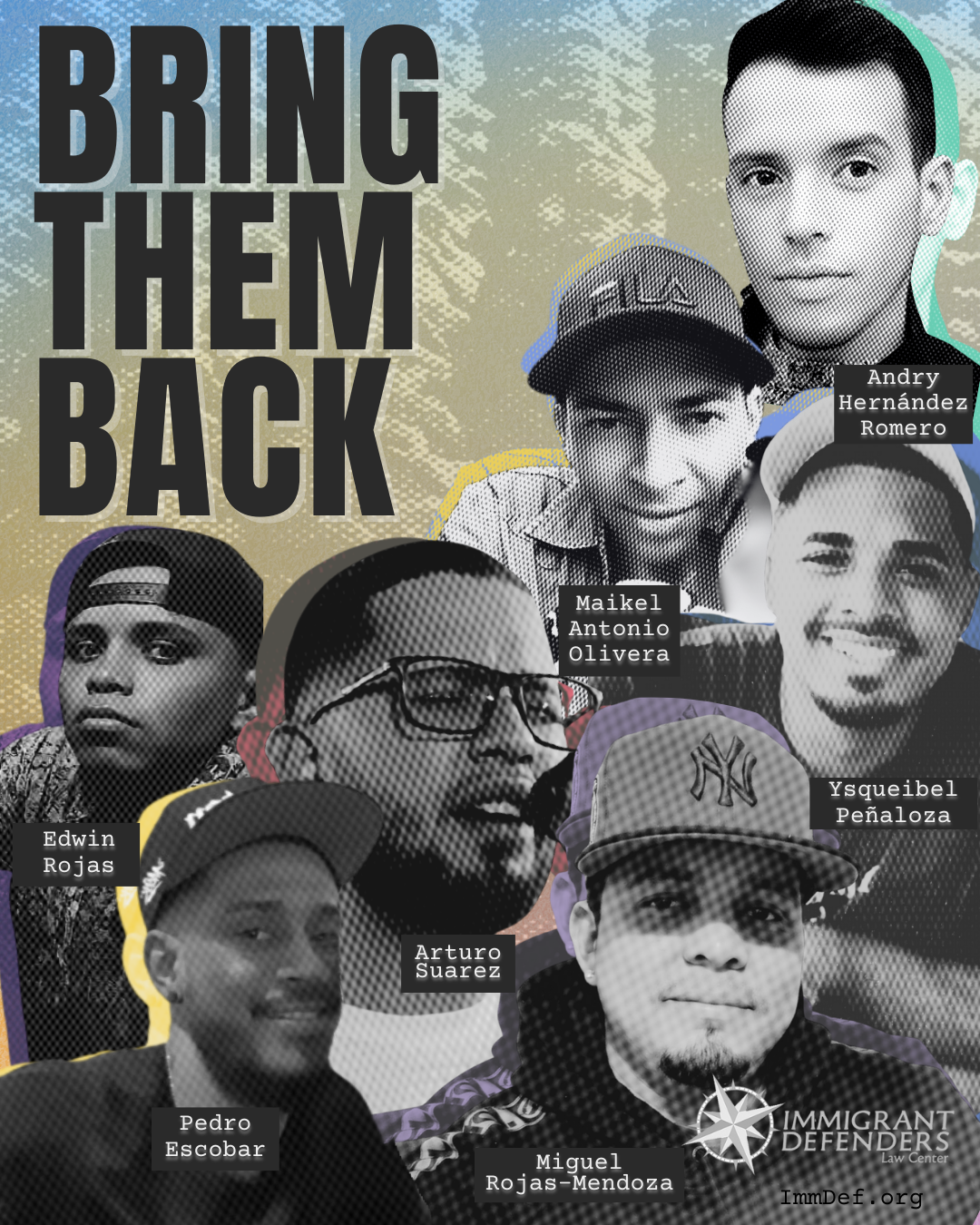

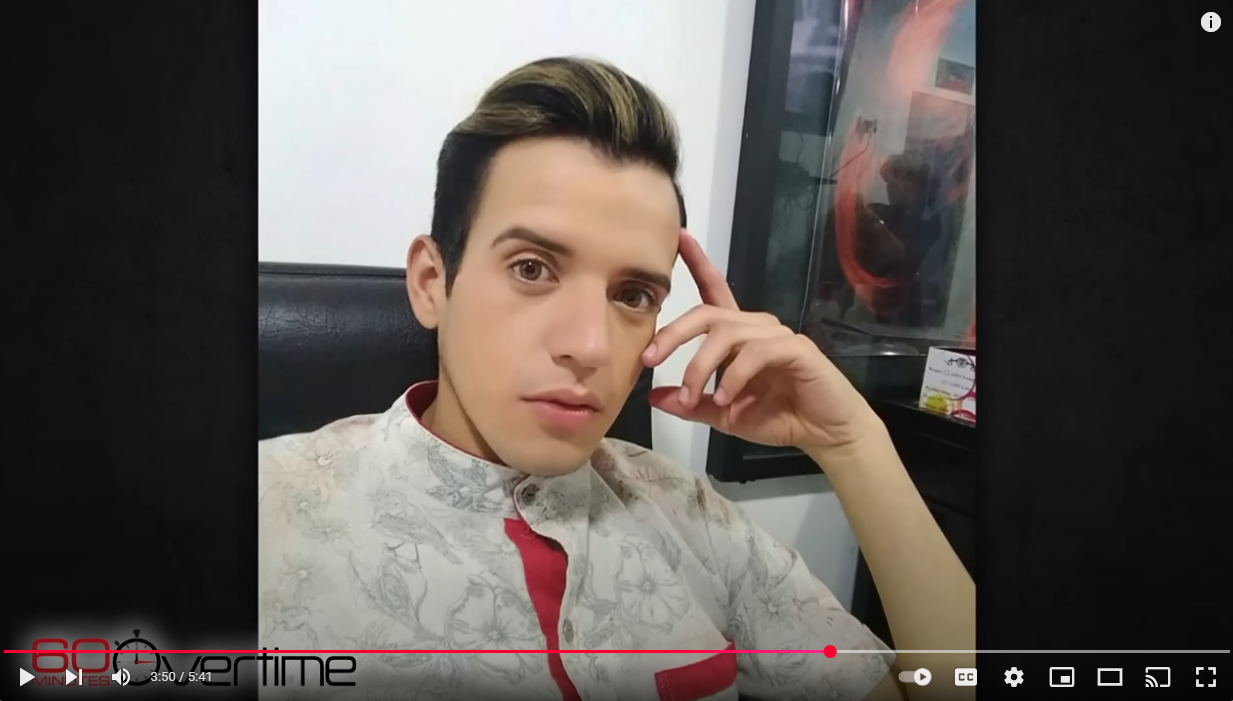

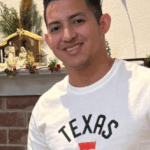

Andry Hernández Romero, 31, left his small hometown of Capacho Nuevo, Venezuela for the United States in May 2024. Like many migrants, he began a long trip through the Darién jungle on the border between Colombia and Panama, on his journey to Mexico.

According to court documents filed by his lawyers, obtained by BBC Mundo, surrendered at the border, at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, on August 29, 2024, after making an appointment with the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency for asylum. His asylum request claimed that he was a victim of persecution in Venezuela for his political beliefs and sexual orientation.

He was then taken into custody by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an agency within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and was sent to the Otay Mesa Detention Centre in San Diego. At the center, “he was flagged as a security risk for the sole reason of his tattoos”, his lawyer wrote in a statement. One of Andry’s friends, Reina Cárdenas, maintained contact with him until a few days before his deportation. She showed BBC Mundo official documents indicating that the young man had no criminal record in Venezuela.

CoreCivic (a private security company contracted by ICE) official Arturo Torres, acting as interviewer, used a score system to determine whether a detainee is part of a criminal organization. It has nine categories, each with its own score. According to the criteria, the detainees are considered gang members if they score 10 or more points, and they are considered suspects if they score nine or fewer points.

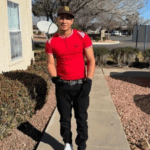

Andry was given five points for the tattoos on his wrists, which included two crowns, according to paperwork signed in December 2024 by officers from the company.

The interviewing officer wrote: “Detainee Hernández has a crown on each one of his wrist. The crown has been found to be an identifier for a Tren de Aragua gang member”.

Andry designed and hand-embroidered his own costumes for the annual religious festival known as the Three Wise Men of Capacho, his family says. The symbol that identifies the religious festival – which was officially declared part of Venezuela’s national cultural heritage, and of which its residents are proud – is a golden crown, and Andry’s tattoos were in in honor of the festival.

“So far, that form [mentioning the crown tattoos] is the only government document linking Mr Hernández to the Tren de Aragua,” Lindsay Toczylowski, executive director of the Immigrant Defenders Law Centre and part of the legal team representing the young Venezuelan, told BBC Mundo.

Venezuelan researcher and journalist Ronna Rísquez, author of a book about Tren de Aragua, dismisses the idea that tattoos are a criterion that defines membership in this group. “Equating the Tren de Aragua gang with Central American gangs in terms of tattoos is a mistake,” she warned.

Unaware that he was suspected of belonging to Tren de Aragua, Andry was expecting to appear in a US court for another asylum-related hearing that he hoped could eventually allow him to remain in the country. By March 2025, he had spent nearly six months at the San Diego detention center before being abruptly transferred to the Webb County Detention Centre in Laredo, Texas, while his asylum case was still pending.

On 15 March, without being able to contest the charges of gang membership, Andry was deported that day as part of a group of 238 Venezuelans and 23 Salvadorans, to El Salvador’s notorious mega-prison, known as the Terrorist Confinement Centre (Cecot).

Since then, no-one has heard from him. His parents had no information about him until they were told that someone had seen a photo of their son in a Salvadoran prison.

The last known image of Andry is a photo taken of him on the night of 15 March inside the Salvadoran mega-prison, when a American photojournalist Philip Holsinger documented the arrival of a group of alleged criminals for Time magazine. That was when he took a photo of a young man saying “I’m not a gang member. I’m gay. I’m a barber”, Mr. Holsinger wrote in his article. The man was chained and, on his knees, while the guards shaved his head. Mr. Holsinger later learned that man was Andry Hernandez. “He was being slapped every time he would speak up… he started praying and calling out, literally crying for his mother,” Holsinger told CBS. “Then he buried his face in his chained hands and cried as he was slapped again.”

Andry’s case has received much attention in the US and mystery surrounds his condition and whereabouts. California Governor Gavin Newsom has requested his return, while four US congressional representatives travelled to El Salvador and requested to be provided with proof of life for him. They did not get it.

ON May 14th, Homeland Security Secretary Kristy Noem refused to give proof of life for Andry during questioning in a House Homeland Security Committee. Representative Robert Garcia asked Noem, “His mother just wants to know if he’s alive. Can we do a wellness check on him?”

Noem replied that she did not “know the specifics” of the case and because he was in El Salvador, Garcia should ask the government there about his wellbeing. The case “isn’t under my jurisdiction,” she added.

There have been recent protests and press conferences for Andry’s release. For example, elected officials, attorneys, and immigrant and LGBTQ advocates gathered to demand his immediate Stonewall Inn on Friday, May 9th, and a Free Andry as show sponsored by : A Crooked/The Bulwark Fundraiser At WorldPride will be at Lincoln Theatre in Washington, D.C. on Friday, June 6.

Additionally, “Andry recently became a named plaintiff in J.G.G. v Trump, a case led by the ACLU that aims to release him and hundreds of Venezuelan men from detention in El Salvador’s notorious CECOT prison,” said Lindsay Toczylowski, president and CEO of the Immigrant Defenders Law Center, which is representing Andry.

Articles:

Andry Hernández Romero, de 31 años, salió de su pequeño pueblo natal, Capacho Nuevo, Venezuela, rumbo a Estados Unidos en mayo de 2024. Como muchos migrantes, emprendió un largo viaje a través de la selva del Darién, en la frontera entre Colombia y Panamá, en su camino hacia México.

Según documentos judiciales presentados por sus abogados y obtenidos por BBC Mundo, Andry se entregó en la frontera, en el Puerto de Entrada de San Ysidro, el 29 de agosto de 2024, tras agendar una cita con la Oficina de Aduanas y Protección Fronteriza (CBP) de EE. UU. Su solicitud de asilo afirmaba que era víctima de persecución en Venezuela por sus creencias políticas y su orientación sexual.

Posteriormente fue detenido por el Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE), una agencia del Departamento de Seguridad Nacional (DHS), y fue enviado al Centro de Detención de Otay Mesa en San Diego. En dicho centro, “fue señalado como un riesgo de seguridad únicamente por sus tatuajes”, escribió su abogada en una declaración. Una amiga de Andry, Reina Cárdenas, mantuvo contacto con él hasta pocos días antes de su deportación. Ella mostró a BBC Mundo documentos oficiales que indicaban que el joven no tenía antecedentes penales en Venezuela.

Un funcionario de CoreCivic (empresa privada de seguridad contratada por ICE), Arturo Torres, actuó como entrevistador utilizando un sistema de puntuación para determinar si un detenido pertenece a una organización criminal. El sistema tiene nueve categorías, cada una con su propia puntuación. Según los criterios, los detenidos son considerados miembros de pandillas si acumulan 10 puntos o más, y sospechosos si obtienen nueve puntos o menos.

A Andry se le asignaron cinco puntos por los tatuajes en sus muñecas, que incluían dos coronas, según documentos firmados en diciembre de 2024 por funcionarios de la empresa. El oficial escribió: “El detenido Hernández tiene una corona en cada muñeca. La corona ha sido identificada como símbolo de pertenencia a la pandilla Tren de Aragua”.

Según su familia, Andry diseñaba y bordaba a mano sus propios disfraces para la festividad religiosa anual conocida como Los Reyes Magos de Capacho. El símbolo que representa esta festividad —declarada patrimonio cultural de Venezuela— es una corona dorada, y los tatuajes de Andry eran en honor a esa tradición.

“Hasta ahora, ese formulario [que menciona los tatuajes de coronas] es el único documento gubernamental que vincula al Sr. Hernández con el Tren de Aragua”, dijo Lindsay Toczylowski, directora ejecutiva del Immigrant Defenders Law Center y parte del equipo legal que representa al joven venezolano, en declaraciones a BBC Mundo.

La investigadora y periodista venezolana Ronna Rísquez, autora de un libro sobre el Tren de Aragua, rechaza la idea de que los tatuajes sean un criterio para definir la pertenencia a ese grupo. “Equiparar al Tren de Aragua con las pandillas centroamericanas en cuanto a tatuajes es un error”, advirtió.

Sin saber que era sospechoso de pertenecer al Tren de Aragua, Andry esperaba comparecer en una nueva audiencia de asilo en EE. UU., con la esperanza de poder permanecer en el país. Para marzo de 2025, ya llevaba casi seis meses en el centro de detención de San Diego antes de ser trasladado repentinamente al Centro de Detención del Condado de Webb en Laredo, Texas, mientras su caso aún seguía pendiente.

El 15 de marzo, sin haber podido impugnar las acusaciones de pertenencia a una pandilla, Andry fue deportado ese mismo día como parte de un grupo de 238 venezolanos y 23 salvadoreños hacia la notoria mega prisión de El Salvador, conocida como Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT).

Desde entonces, nadie ha vuelto a saber de él. Sus padres no tenían información sobre su paradero hasta que alguien les dijo que habían visto una foto de su hijo en una prisión salvadoreña.

La última imagen conocida de Andry fue tomada la noche del 15 de marzo dentro del CECOT, cuando el fotoperiodista estadounidense Philip Holsinger documentó para la revista Time la llegada de un grupo de supuestos criminales. En su artículo, Holsinger relató que un joven dijo: “No soy pandillero. Soy gay. Soy barbero”. El hombre estaba encadenado y de rodillas mientras los guardias le rapaban la cabeza. Más tarde, Holsinger supo que ese hombre era Andry Hernández. “Lo abofeteaban cada vez que intentaba hablar… empezó a rezar y a llamar, literalmente llorando por su madre”, dijo Holsinger a CBS. “Después enterró su rostro entre sus manos encadenadas y lloró mientras lo golpeaban de nuevo”.

El caso de Andry ha recibido gran atención en EE. UU. y sigue rodeado de misterio sobre su estado y paradero. El gobernador de California, Gavin Newsom, ha solicitado su repatriación. Cuatro congresistas estadounidenses viajaron a El Salvador para pedir una prueba de vida, pero no obtuvieron respuesta.

El 14 de mayo, la secretaria de Seguridad Nacional, Kristy Noem, se negó a dar prueba de vida durante una audiencia en el Comité de Seguridad Nacional de la Cámara. El representante Robert Garcia le preguntó: “Su madre solo quiere saber si está vivo. ¿Podemos hacer un chequeo de bienestar?”. Noem respondió que no conocía los detalles del caso y que, al estar en El Salvador, Garcia debía preguntar al gobierno salvadoreño sobre su situación. Añadió que el caso “no estaba bajo su jurisdicción”.

Recientemente ha habido protestas y ruedas de prensa exigiendo la liberación de Andry. Por ejemplo, funcionarios electos, abogados y defensores de inmigrantes y personas LGBTQ se reunieron el viernes 9 de mayo en el Stonewall Inn para exigir su liberación inmediata. También se realizará un evento llamado “Free Andry” patrocinado por A Crooked/The Bulwark Fundraiser, en el Lincoln Theatre de Washington D.C. el viernes 6 de junio.

Además, “Andry se convirtió recientemente en demandante principal en el caso J.G.G. v Trump, una demanda liderada por la ACLU que busca liberar a él y a cientos de venezolanos detenidos en la prisión CECOT en El Salvador”, afirmó Lindsay Toczylowski, presidenta y directora ejecutiva del Immigrant Defenders Law Center, que representa a Andry.