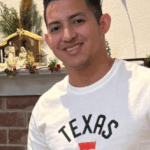

Before moving to the U.S. in 2023, Merwil Gutierrez Flores lived with his family a town near Caracas, Venezuela and went to school. His father, Wilmer, worked for two jobs to support his loved ones, which included Merwil’s grandmother, who was battling cancer, and his three children: his son Merwil and his daughter Wisleidy, and his youngest daughter Wiskelly who lived with her mother in Perú.

But none of those jobs were enough to cover even the most basic expenses. “With how things were going in Venezuela, your monthly salary wasn’t even enough to buy food,” Gutiérrez says. So, when Merwil finished school, Wilmer decided, they would begin their journey toward the American dream — a place where they could have a more stable and better life.

On May 19, 2023, Wilmer, Merwil, and Merwil’s cousin, Luis began their journey to the US. The journey lasted about a month until they reached Ciudad de Juárez, a town in Mexico near the U.S. border. From there, they applied for an appointment to seek humanitarian parole using the CBP One app. They waited one week until they were able to secure an appointment with immigration authorities Wilmer recalls that they slept outside that night, right on the U.S. border. They had to do it to avoid losing their place in the long line that formed outside the immigration office each day.Once inside the US, they reported to the authorities and opened an asylum case.

They were first sent to a shelter in Texas, then transferred to Denver, and eventually took bus tickets to New York where they ended up in an industrial shed near JFK Airport that had been repurposed as a shelter. “It looked like a hospital ward,” Wilmer recalled, describing the rows of small sleeping couches lined up side by side. From there, after they got work permission, they began searching for jobs. “Every day, we’d walk around Manhattan and nearby areas, asking people if they knew of any job openings,” he says. After two weeks of the same routine, a friend gave them a tip: if they went to some warehouses near JFK at night, there would almost always be work available.

They got jobs at a warehouse in July. The job operated through a large WhatsApp group, where the boss would send out the nightly schedule — listing the names of those selected for the 9:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. shift. The Gutiérrez family worked at least six nights a week, earning $140 per shift. “My son and I slept during the day and worked at night. There was never time for parties or anything like that. We’d just go back to the apartment in the Bronx, the one we found through a friend, which we shared with people we didn’t even know, and lock ourselves in our room until the next shift came around,” Merwil’s father said.

Then on February 24, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained Merwil while he was outside the apartment. He had no criminal record, neither in Venezuela nor the U.S., nor did he have any tattoos — one of the features that the U.S. police used to link them to the Tren de Aragua gang. But none of that stopped him from being arrested. Wilmer only found out his son had been detained after receiving a phone call on February 24 from his nephew, Luis, who lives with them. Luis saw ICE take Merwil from a window in their apartment. Merwil was on his way back from work, just steps from his home, when ICE agents stopped him. “The officers grabbed him and two other boys right at the entrance to our building.

One said, ‘No, he’s not the one,’ like they were looking for someone else. But the other said, ‘Take him anyway,’” Luis said.T

he last time Wilmer spoke to his son was on March 14, during a brief phone call allowed by the police. Merwil told him he was still being held in Pennsylvania and that, apparently, he would be transferred to Texas and then sent back to Venezuela. But that never happened.It was only after seeing a news report listing the 238 Venezuelans detained that Gutiérrez found out his son was one of the men sent to the mega prison in El Salvador. According to William Parra, an immigration attorney from Inmigración Al Día, the law firm representing Merwil’s case, his detention was unjustified since he currently has an immigration court case pending with his father and was showing up to court and doing the right things. “Merwil was at the wrong place at the wrong time. ICE was not looking for him, nor is there any evidence whatsoever that Merwil was in any gang.”

#bluetrianglesolidarity

Antes de mudarse a los EE. UU. en 2023, Merwil Gutierrez Flores vivía con su familia en un pueblo cerca de Caracas, Venezuela y asistía a la escuela. Su padre, Wilmer, trabajaba en dos empleos para mantener a sus seres queridos, que incluían a la abuela de Merwil, que luchaba contra el cáncer, y sus tres hijos: su hijo Merwil y su hija Wisleidy, y su hija menor Wiskelly que vivía con su madre en Perú.

Pero ninguno de esos trabajos era suficiente para cubrir ni siquiera los gastos más básicos. “Con la situación en Venezuela, tu salario mensual no era suficiente ni siquiera para comprar comida”, dice Gutiérrez. Así que, cuando Merwil terminó la escuela, Wilmer decidió que comenzarían su viaje hacia el sueño americano: un lugar donde podrían tener una vida más estable y mejor.

El 19 de mayo de 2023, Wilmer, Merwil y el primo de Merwil, Luis, comenzaron su viaje hacia los EE. UU. El viaje duró aproximadamente un mes hasta que llegaron a Ciudad Juárez, un pueblo en México cerca de la frontera con los EE. UU. Desde allí, solicitaron una cita para buscar un permiso humanitario utilizando la aplicación CBP One. Esperaron una semana hasta que pudieron asegurar una cita con las autoridades de inmigración. Wilmer recuerda que durmieron afuera esa noche, justo en la frontera con los EE. UU. Tuvieron que hacerlo para evitar perder su lugar en la larga fila que se formaba afuera de la oficina de inmigración cada día. Una vez dentro de los EE. UU., se presentaron a las autoridades y abrieron un caso de asilo.

Primero fueron enviados a un refugio en Texas, luego trasladados a Denver, y finalmente tomaron boletos de autobús a Nueva York, donde terminaron en un cobertizo industrial cerca del aeropuerto JFK que había sido reacondicionado como refugio. “Parecía una sala de hospital”, recordó Wilmer, describiendo las filas de pequeños sofás para dormir alineados uno al lado del otro. Desde allí, después de obtener permiso de trabajo, comenzaron a buscar empleo. “Todos los días, caminábamos por Manhattan y áreas cercanas, preguntando a la gente si sabían de alguna oferta de trabajo”, dice. Después de dos semanas de la misma rutina, un amigo les dio un consejo: si iban a unos almacenes cerca de JFK por la noche, casi siempre habría trabajo disponible.

Consiguieron empleo en un almacén en julio. El trabajo se organizaba a través de un gran grupo de WhatsApp, donde el jefe enviaba el horario nocturno, enumerando los nombres de los seleccionados para el turno de 9:00 p.m. a 6:00 a.m. La familia Gutiérrez trabajaba al menos seis noches a la semana, ganando $140 por turno. “Mi hijo y yo dormíamos durante el día y trabajábamos por la noche. Nunca había tiempo para fiestas ni nada por el estilo. Solo regresábamos al apartamento en el Bronx, el que encontramos a través de un amigo, que compartíamos con personas que ni siquiera conocíamos, y nos encerrábamos en nuestra habitación hasta que llegaba el próximo turno”, dijo el padre de Merwil.

Luego, el 24 de febrero, la Oficina de Inmigración y Aduanas (ICE) detuvo a Merwil mientras estaba fuera del apartamento. No tenía antecedentes penales, ni en Venezuela ni en los EE. UU., ni tenía tatuajes, una de las características que la policía de EE. UU. usaba para vincularlos con la banda Tren de Aragua. Pero nada de eso impidió que fuera arrestado. Wilmer se enteró de que su hijo había sido detenido después de recibir una llamada telefónica el 24 de febrero de su sobrino, Luis, que vive con ellos. Luis vio a ICE llevarse a Merwil desde una ventana de su apartamento. Merwil estaba regresando del trabajo, a pocos pasos de su casa, cuando los agentes de ICE lo detuvieron. “Los oficiales lo agarraron a él y a otros dos chicos justo en la entrada de nuestro edificio. Uno dijo: ‘No, él no es el indicado’, como si estuvieran buscando a otra persona. Pero el otro dijo: ‘Llévatelo de todos modos’”, dijo Luis.

La última vez que Wilmer habló con su hijo fue el 14 de marzo, durante una breve llamada telefónica permitida por la policía. Merwil le dijo que todavía estaba detenido en Pensilvania y que, aparentemente, lo trasladarían a Texas y luego lo enviarían de regreso a Venezuela. Pero eso nunca sucedió. Fue solo después de ver un informe de noticias que enumeraba a los 238 venezolanos detenidos que Gutiérrez se enteró de que su hijo era uno de los hombres enviados a la mega prisión en El Salvador. Según William Parra, un abogado de inmigración de Inmigración Al Día, el bufete de abogados que representa el caso de Merwil, su detención fue injustificada ya que actualmente tiene un caso pendiente en la corte de inmigración con su padre y estaba compareciendo ante la corte y haciendo lo correcto. “Merwil estaba en el lugar equivocado en el momento equivocado. ICE no lo estaba buscando, ni hay ninguna evidencia de que Merwil estuviera en alguna banda”.

Leave a Reply